“. . . one might think that the Crescenta Valley is a terrible place to live. It isn’t — in fact, it’s better than most places. The truth is that any community could easily spawn several local history books of similar evil nature. Most communities choose not to. Most communities want to see only the good sides of their histories. But not the Crescenta Valley. Our history is so dynamic and colorful that to only cover the ‘good’ aspects would not do it justice.”

~ Wicked Crescenta Valley, Gary Keyes and Mike Lawler

Glendale had 0 Black residents in 1910.

In 1960, 62.

Today? 3,230

1.6% in 2000, 1.6% in 2010.

Glendale was a sundown town. Decidely.

I’d heard about Glendale’s racist history, of course, even wrote a little about it during my first year at the paper.

At a meeting at the beginning of June, each member of the Glendale city council reacted to the murder of George Floyd beneath the knee of Minneapolis police. I reported their remarks in the Crescenta Valley Weekly that week Budget and Policing Policies Discussed by Council:

At the beginning of the Council’s evening meeting, Councilmember Ara Najarian read from a prepared statement, apologizing for comments he had made on social media, emphasizing that he is not against protesting nor the free expression of speech but that there had been credible threats made against Glendale targets. He acknowledged that his comments may have taken away from those wanting to mourn the death of George Floyd and to protest against racism.

“I look forward to the candlelight vigil rescheduled [on] June 7,” he said. “I intend to stand in solidarity against the injustices we have witnessed.”

Mayor Vrej Agajanian expressed his “shock and surprise” of the incident. He quoted extensively from a June 1995 Dept. of Justice document which delineates the treatment of handcuffed people and asked Glendale police chief Carl Povilaitis to explain “how it works here.”

Devine read a statement condemning “police brutality.” Brotman began a long, heartfelt personal statement saying that he is “horrified by the state-sanctioned murder,” recalling Glendale’s “dark history as a sundown town, the western headquarters of the Nazi party into the ’80s, with an office on Brand Boulevard.”

Councilmember Ardashes “Ardy” Kassakhian shared Brotman’s horror at the city’s racist past.

“I am not a perfect person. I try to teach my son to be a better person than I am,” he said. “We teach him to follow ‘I’m sorry’ with ‘How can I help?’ We need to do better to make people of color feel welcome in our city, to denounce our past. We are not that city anymore.”

He ended with, “I’m sorry. How can I help?”

Povilaitis reached back across his “three decades” of police experience.

“This is extremely disturbing. What I see there is wrong. I can’t say it any simpler than that. The chiefs I’ve spoken to all agree. This is wrong. It is not in keeping with the training or expectations of a professional, world-class police department. I tell every potential recruit that we perform respectful, constitutional policing that respects everyone’s rights,” he said. “And we are steeped in the traditions of community policing. This is my community and I want it to be one where everyone is welcome and safe.”

The police chief detailed the department’s response to threats it received over the weekend, outreach done to organizations across the city, and 39 arrests made in the past few days (for curfew violations, burglary and receiving stolen property). He answered a question about the department’s use of “chokeholds and strangleholds.”

“As long as I’ve been on this department, these have never been authorized as any use of force,” he said.

This discussion of Glendale’s racist past made me even more curious.

How bad was it, really?

Really bad.

Glendale Community College’s El Vaquero’s Jane Pojawa reported on a Bad Glendale tour in June 2010, organized by local historian Gary Keyes:

Klan membership was still enough of a campus problem that the Sept. 30, 1936, Galleon, soon to be renamed El Vaquero, warned students that their participation in such an organization would not be tolerated. “It is rumored that a certain group of freshman (sic) have organized into a semi-secret group that is known as the ‘Clansmen,” stated the editorial. “Societies of this kind work against the best interests of the school and no loyal student should become affiliated with any such group.”

Pervasive racism occurred at the high school level as well. In a 1936 football game in which Glendale High was competing against Pasadena High for league championship, Jackie Robinson, later to become one of the outstanding figures in baseball, was targeted and viciously attacked by the Glendale team. His injuries were sufficient to require hospitalization, and the demoralized Pasadena team lost.

As late as 1962, the Ku Klux Klan marched on Brand Boulevard with a horse brigade, marching band and burning cross.

And from Glendale Forward:

Many residents newer to the area are unfamiliar with the more awful parts of Glendale’s history. We’d like to change that, because in many ways, the legacy of the city’s bigoted, “whites only” past is still with us. In one alarming example in 2014 in Montrose, a Black private investigator was pulled over for tinted windows by the LA County Sheriff’s deputy, who immediately drew his gun on the investigator.

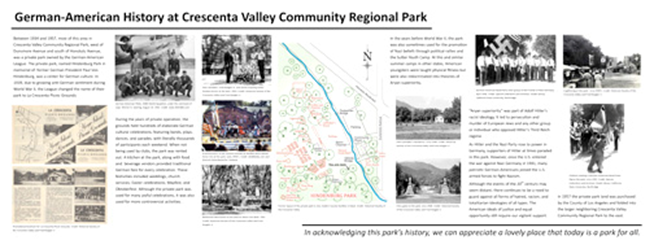

For most of the 20th century, there was a pervasive racist presence in Glendale; this ranged from outright Nazi rallies for the German American Bund chapter in La Crescenta in the 1930s, to the KKK in the second half in the 20th century. Indeed, the recently proposed (and ultimately removed, thanks to some activists) “Hindenburg Park” sign is evidence that too many Glendale residents are still unaware of this past.

An old friend recalled her days at Occidental College in the late sixties: “When I was at Oxy, we were advised to steer clear of Glendale!”

In retrospect, she regrets sending her Black daughter to public high schools in Glendale (even the esteemed Crescenta Valley High) and recounts her being stopped by the cops for “looking out of place” so often that they got to know her.

“If you were Black, you only went through Glendale if you were waiting for the 92 or 94 bus to go to downtown LA or Pacoima or the 180/181 to go to Hollywood or Pasadena. And you did it before sundown. That was true well into the 1990’s,” another person commented on Twitter.

In 2017, I reported on a piece of Glendale’s troubled history at the end of the Crescenta Valley Park sign saga:

“In early February 2016, a large wooden sign sprouted up at the intersection of Dunsmore and Honolulu avenues, announcing the entrance to the park, naming it Hindenburg Park. Written in large Gothic German font, the sign said, “Willkommen zum” – “welcome” in German, and it caused an immediate reaction in the community,” I reported the history and the compromise reached about the offensive sign in August 2017: Sign Remembers Past at CV Park

The sign was removed on May 4, 2016.

“The Commission and the County took the issue seriously and worked hard to be objective,” Jason Moss, executive director of the Jewish Federation of the Greater San Gabriel and Pomona Valleys, recounted. “The ad hoc committee delved deep into the language with the help of a quality mediator and the positive results show that we can come together through respectful dialog.”

Here’s the historic marker that’s there now:

I’m inspired by the Black Lives Matter peaceful marches and rallies, particularly those specifically in Glendale.

Joe Kahraman and I started talking about the influence of the Armenian diaspora on the politics, demographics, and tolerance of Glendale. Together, we kvelled about Arpi Movsesian’s spot-on op ed Black Lives Should Matter to the Armenian Diaspora:

“An article from 1994 in the Los Angeles Times refers back to a history not known to many Glendale Armenians: Glendale as grounds for abundant Ku Klux Klan activity in the 1920s, curfews for black people in the 1950s, and as a West Coast headquarters for the American Nazi Party, as well as for other nationalist organizations. Glendale Armenians, living in a city that from 1906 to this day has not had one black individual as its mayor or on its board of trustees, should tread extremely carefully on these grounds, while acknowledging their privileged position. As Armenians, we should understand that our ‘whiteness’ and colorism in general, is a construct that Armenians, who arrived in California after the Genocide and were heavily discriminated against (being called ‘dirty black Armenian,’ ‘low class Jew,’ and ‘Fresno Indian’) had to fight for in an ongoing battle of the construction and re-construction of race.”

I was amazed to discover I live in an ethnoburb.

Then I read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism and found Glendale in way too many references and citations. Just one example:

“Glendale, California, is a suburb of Los Angeles, but it lies ‘about an hour’s drive’ from Watts, according to a woman who attended high school in Glendale in the mid-1960s. One day, playing tennis after school, she was ‘shocked to see what appeared to be an incredibly large contingen[t] of National Reserve soldiers! There were tanks, tents, trucks and a lot of soldiers.’ City officials of this sundown suburb had called out the National Guard to protect Glendale during the Watts riot — from what, they never specified.”

~ James W. Loewen, Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism

The Numbers Don’t Lie

How ‘bout yours? Was it a sundown town? Check here. Or here.

Want more information? Here’s a map: Sundown towns map and some other reliable resources: Sundown Town resources

Is Glendale still a sundown town? How welcoming and comfortable do African Americans living here feel?

The last section of Loewen’s book lists solutions and remedies, reparations, process for truth and reconciliation.

Activists in Glendale have organized Black in Glendale, the Glendale Community College coordinated a week-long forum mid-June, Deconstructing Racism: A Persistent American Challenge; there’s talk of a town hall or forum or something forward looking and positive. Turnout for the last municipal election surpassed that of any past municipal voter participation and will continue to increase based on the change in timing of these elections. The new council is the most progressive ever elected. That trend will also continue.

Glendale’s past is ugly. What about its future?

“To end our segregated neighborhoods and towns requires a leap of the imagination: Americans have to understand that white racism is still a problem in the United States. This isn’t always easy. Most white Americans do not see racism as a problem in their neighborhood. We need to know about sundown towns to know what to do about them.”

~ James W. Loewen, Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism